Your next GREAT

adventure to Bhutan

starts here

Travel with bhutan's best tour operator

Experience the real Bhutan

THE LAND OF HAPPINESS

We help you plan your perfect trip to Bhutan

Always Bhutan Travel is a bespoke local tour company specialized in, exclusive tailor-made journeys to Bhutan that are perfect for adventure enthusiasts, cultural tours, small group journeys, and family holidays.

Whether you yearn for thrilling treks amidst pristine landscapes, immersive cultural encounters in the Himayas, or unique family bonding experiences, we design your dream Bhutanese escape.

Discover the Last Himalayan Kingdom on Earth with us, where authenticity and unforgettable memories await.

One-of-a-Kind

Exotic Destination

10 Years Offering

Life Changing Adventures

Private &

Small-Group Adventures

Popular tour packages

5/5

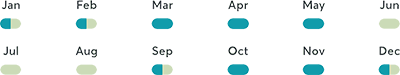

March-May and September-November

- The weather is simply best in spring and autumn.

- The view of the Himalayas is excellent in November.

- The rhododendrons bloom in March and April.

3/5

December, January & February

The weather is very sunny and clear, but it can get very cold at night.

4/5

June-August

- Lots of rain and not recommended for hiking and trekking trips.

- The flowers in the mountains bloom in all their glory.

- Ideal for cultural trips and museums